Sadia Pineda Hameed + Beau W Beakhouse

Rustic Futures

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, detail from it resonates like spalting wood (2021). Image courtesy the artists.

Is there a tension there between moving past legacies of colonialism and the experience of being ‘new’? There’s a coming together, but it’s absolutely in the tension. Toolmaking can be understood as an embodiment of this tension, where the drive for productivity can meet the friction of unreadability.

The collaborative practice of Sadia Pineda Hameed and Beau W Beakhouse is a technical talisman, a blueprint for navigating unsettled pasts and future histories, a linguistic shapeshifter. Currently based in the Ebbw Valley in Wales, the duo have worked together since 2016, building up a body of work that morphs across media: from performance- lectures to radio broadcasts, DIY publishing to green woodworking. In the blending of anti- colonial tools and tactics of resistance with alternative fabrication techniques, their work proposes autonomous forms of communication, knowledge-sharing, and craft.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, installation view of Ornaments of Prospect (2023). Image courtesy the artists, copyright Simon Mills.

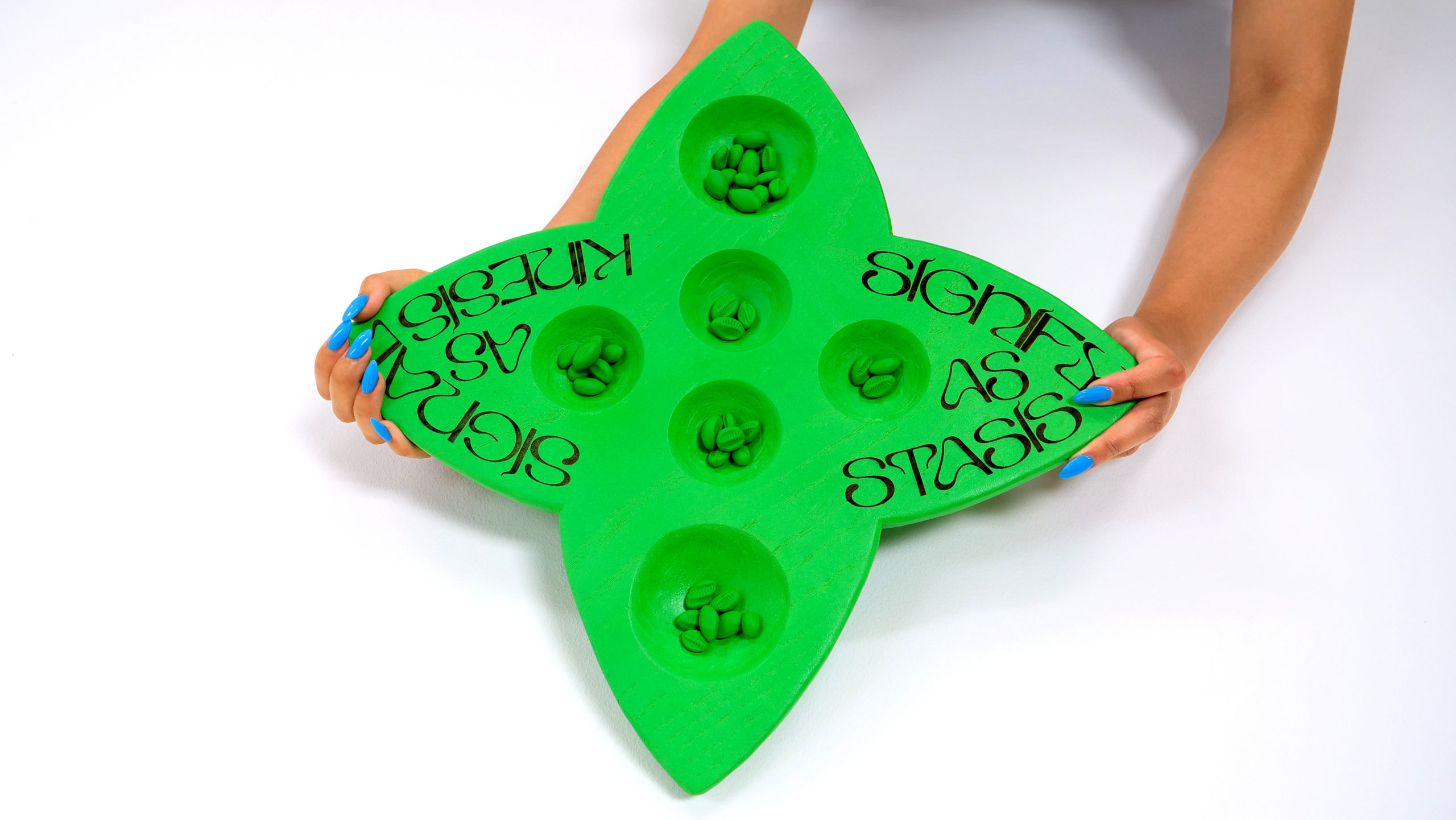

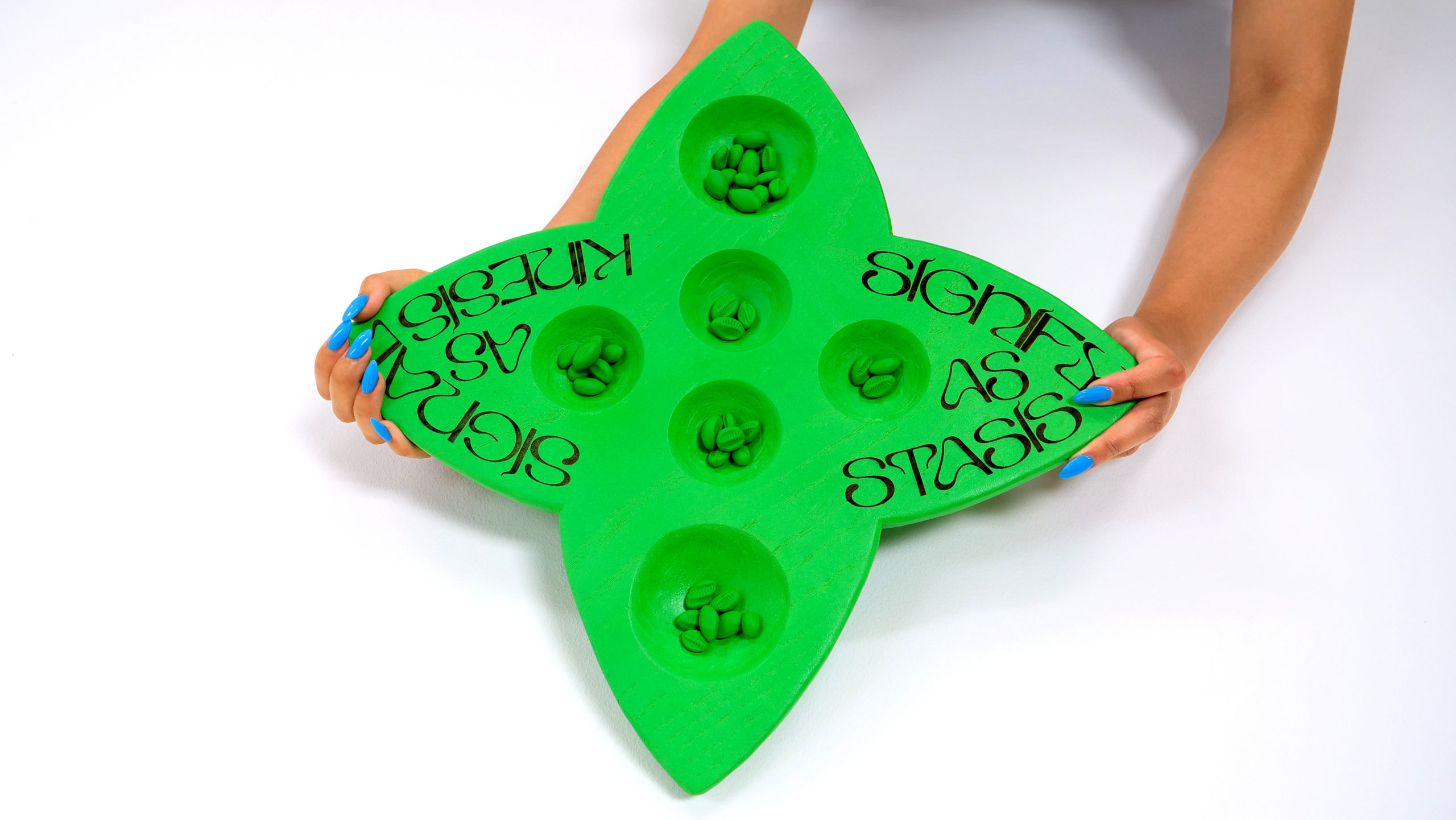

“When you’re trying to build worlds, you’re always lacking the language that you need,” suggests Pineda Hameed. “It’s both enough and never quite enough. We are constantly seeking out other methods of making that language.” So far, these methods have taken the form of a sci-fi green-screen room complete with hovering Filipino board games (it resonates like spalting wood, 2021), a future-rustic iteration of the same game rooted in green woodworking (adzing planes like waning moons, 2022) and metallic anti-tools that refuse to reveal their function (Ornaments of Prospect, 2023). An interest in the generative potential of play and speculative fiction strategies suffuse their work with a kind of corrosive logic: each project suggests an operating system that dissolves just before it’s rendered legible.

It’s not just about the (re)making of something, but reclaiming and remixing the resonances of these tools and games as strategies of resistance. We’re interested in objects that encourage interpretation and respond to a very high level of specificity. We also like the sense of things being in the middle of nowhere.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, film still from it resonates like spalting wood (2021). Image courtesy the artists.

One project bleeds into the next as the duo reapproach a subject from different angles and materials, exploding the capacities of its meaning. Recent projects have focused on the Filipino board game sungka: a strategy game comparable to chess in which players take and deposit seeds in hand-hewn pits. Like the generative capacity of storytelling detailed in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, the game itself becomes a vessel for layered and collaborative world-making. But in the Filipino context, sungka holds a tension between its colonial heritage and its capacities as an anti-colonial tool for communicating the unspeakable.

Sungka has these traditional forms of storytelling based on shapes and patterns, gestures and movements, what’s said and unsaid. The board is a space where dialogue can flow wordlessly, which has the potential to cross over the colonial boundaries of language.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, installation view of adzing planes like waning moons (2022). Image courtesy the artists.

A redwood falls in a Welsh arboretum. What to do with a death that is also a kind of life, a gesture against its own colonial capture? In adzing planes like waning moons, the sungka board arises again, this time from a green woodworking technique used by Beakhouse’s family, in tribute to the fallen tree. In green woodworking, which manipulates unseasoned wood without power tools, there is no quality control; the log splits as it likes, and imperfections are exalted instead of scrubbed out. “Between the contaminated worlds of capitalism and a mutated nature, we wanted to settle the score through a reparative repurposing of the wood,” Pineda Hameed and Beakhouse explain.

We speculate about the meaning of this unmeaning and what it holds: stillness, resistance, and rest. This is the smell of the spalted ash: the fire or the destruction. Why not make something that comes from destruction, when we already know so much destruction?

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, installation view of adzing planes like waning moons (2022). Image courtesy the artists.

The pair of seats framing the board explicates this process through language: one bench reveals the artists’ secret mission to salvage the redwood from the arboretum, while the other details the exacting methods of extraction that constituted its original capture. Etched upon the sungka table, somehow split between these two worlds, is a manual for future disruptions. “Displace acculturate and liberate stolen trees / make tools to make tools in rustic futures” snakes around the board in a burned-out typeface that merges baroque flourish with high-tech mysticism.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, installation view of adzing planes like waning moons (2022). Image courtesy the artists.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, detail from it resonates like spalting wood (2021). Image courtesy the artists.

Not the rustic as in a romanticized past, but as a production prototype for a future where we each could be responsible for the sustenance of a collective project. As an understanding of the future that is neither naive nor apocalyptic.

In Ornaments of Prospect, the duo’s latest project, these tools got sharper while their frameworks became more opaque. Focusing on the filipino bolo, a device historically used for agriculture and war, they present the tool here only through its offcuts. Realized in unevenly treated metal–brandishing an oil-slick sci-fi sheen at parts, rusting red at others – it becomes a mysterious artifact that refuses to reveal its functionality.

Maybe the moment of trickery is not that the tool inherently does something malicious – but that it is used as a means to an end that isn’t apparent. The rustic is a way to claim ownership of land that has been removed by industrialization and abstraction. It is a site of re-connection, not creation.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, installation view of Ornaments of Prospect (2023). Image courtesy the artists, copyright Simon Mills.

Like an inverted broken hammer theory that ghosts legible meaning through its absence, the bolo exists here as a haunted byproduct. Compared to Pineda Hameed and Beakhouse’s previous projects, there is a defiance to the tool’s inscrutability. It indicates a world-making process that does not, as with the sungka boards, emerge from a porous invitation to play, but from a sharp right to refusal. “We’re interested in shifting what’s necessary in steps of production,” they suggest. “What happens when you have no fluency for a tool, no language to decipher it?”

In many ways, toolmaking is a language already; both technologies offer ways of instrumentalising knowledge of the world around us. By reconfiguring tools and games as sites for refusal and collective meaning-making, Pineda Hameed and Beakhouse open up new anti-colonial tactics for world-making, where any possible future always carries with it a (re)reading of the past, as generative as it is necessary.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, detail from Ornaments of Prospect (2023). Image courtesy the artists, copyright Simon Mills.

I have this dream about free diving in the Philippines and coming across a shipwreck. I find her in the debris of a collision, recycled waterlogged woodcombing spalting in her veins. She’s always resurrected with the unfamiliar syllables of these futuristic oceans, maybe an apostrophe or two.

For a while she swims again with me I watch her move like the swell and whistle of ripples on the surface of my memory. I remember what it was like to know her, though this is still possible. At the end of the dream, which is always in the summer, she has to return to her ocean. I think in her story we can find worlds where the traces left behind are readable as something more than what splinters.

Sadia Pineda Hameed & Beau W Beakhouse, detail from it resonates like spalting wood (2021). Image courtesy the artists.