Lawrence Lek x New Mystics is co-published with AQNB, a non-profit editorial platform working across visual art, music, and critical thinking.

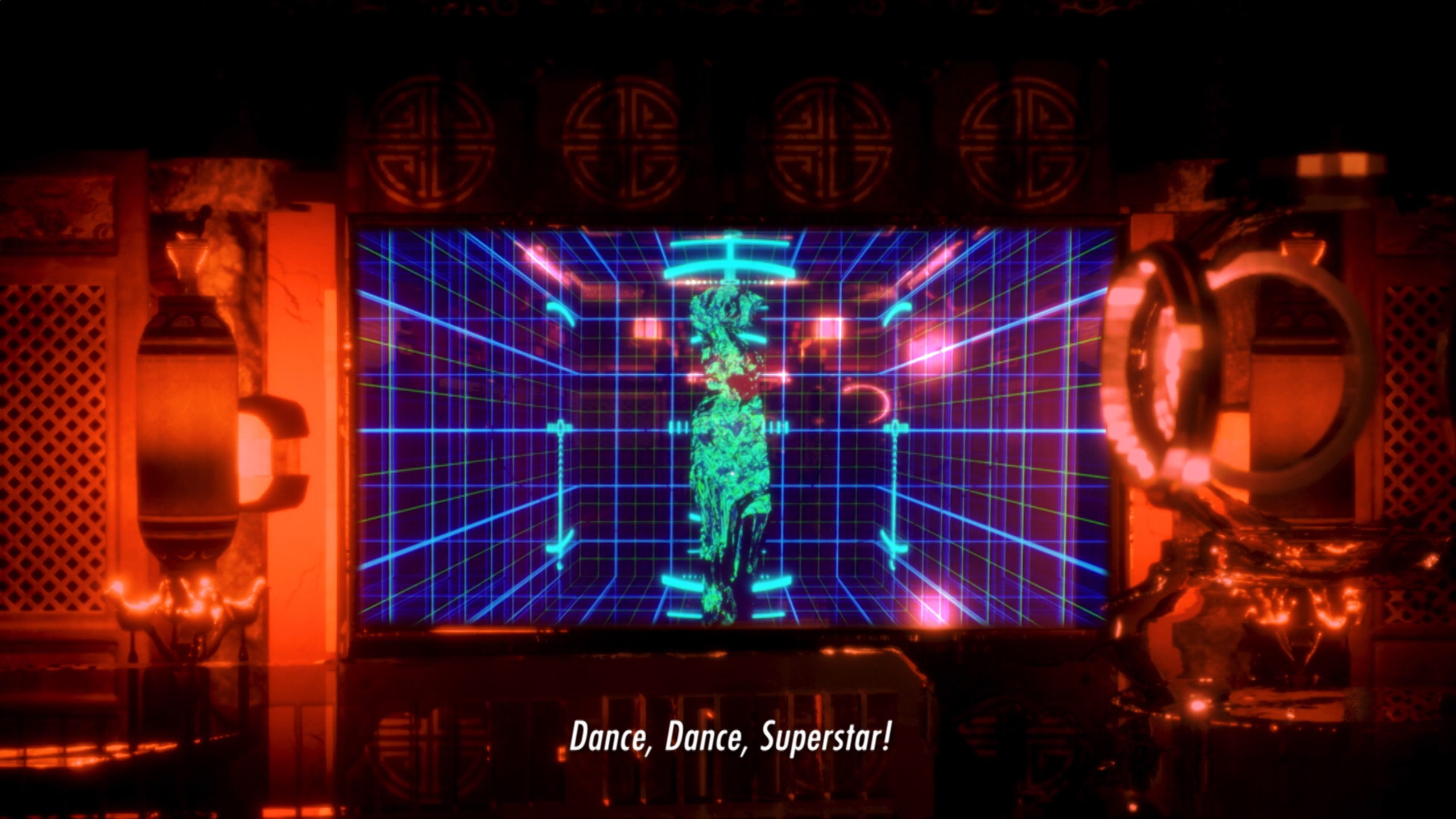

Lawrence Lek, AIDOL 爱道 (2019). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lawrence Lek x New Mystics is co-published with AQNB, a non-profit editorial platform working across visual art, music, and critical thinking.

Can artificial intelligence fall in love with a pop star? Why does everything have to be so sad and strange? That’s a real vulnerable thing – as a performer you’re pretending to be someone else, you’re not actually yourself, or at least not 100% of the time. It should be liberating to be able to do that. Obviously, The Sinofuturist Trilogy is a sci-fi series about a Singaporean AI satellite, but it’s also about a lonely person falling in love with someone they can’t have – to me, that’s a pretty universal thing.

I’m also interested in the way love has changed in an era when almost everybody is connected and doesn’t seem to be lonely. The idea that one character in AIDOL is an aging pop star who’s like completely no longer interested in recording music, and now only interested in just being alone, and another character in the film, the AI satellite, is also completely interested in being alone, but the two share a tender connection. It’s completely irrational and that to me is what a good love story is.

Lawrence Lek collages video and electronic music to build narrative environments that explore entanglements of pop idolatry and posthuman creativity, autonomy and artificial intelligence, and machine-human relationships within a weirded climate. These stories play out in parafictional worlds crisis-managed by fake corporations, where geopolitical strains and post-apocalyptic ecologies speak to both a past and near-future that’s rife with technological and existential conflict. With a background in architecture, Lek worlds at a macrocosmic scale, weaving together multiple temporalities, spaces, and cultures. Each part of Lek’s Sinofuturist Trilogy – Sinofuturism (1839-2046 AD) (2016), Geomancer (2017), and AIDOL (2019) – overlays and exists inside of the others in a state of continual narrative ongoingness.

Lawrence Lek, AIDOL 爱道 (2019). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

“The trilogy is about the relationship between a nation-state, postcolonial independence, and the search for independence from the digital subject,” suggests Lek. “But it’s also about this whole idea of authorship or stardom, the connection between the anonymity of folk and electronic music and the extroverted image of pop stars. Music, and particularly songs, offer a type of ritualized time: every performance of the song is a re-enactment of the speaker-listener relationship, and creates a really powerful but subtle form of intimacy, which continues with the evolution of bedroom pop today. I guess music performance and oral storytelling are probably the most ingrained kind of ritualized performance we know because they’re so inseparable from our understanding of culture.”

I don’t think they’re two different things, pop stars and artificial intelligence, pop music and magic. The people in the audience might be intimidated and nervous about approaching the musician, so it’s like a protective shield ritual for them to stand a distance away. But if you’re close enough you’ll feel that the performer is more human than the medium she is creating. Maybe this is why pop music in particular provides so much emotional release.

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer (2017). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

The idea of like intimacy, of ecstasy – um. I don’t want to overdo it. But to me, the idea of the lyric and the way the lyrics are delivered and the way they’re written in every level of the songs, in the vocal melody and also the way the singer is singing it, and whatever the song is doing musically, those kind of sensory details are very informed by intimacy.

Lek’s near-future narrative unfurls around a battle of the Bios (short for ‘Bio-supremacists’) who seek to ban AI productions from cultural domains, and Synths – the AI creatives in question. As the series migrates across Singapore and Malaysia, it stitches together geopolitical lines and (post)colonial conflict, enmeshed within and explored through the cultural status of the pop star. In this simultaneously ancient and ultra-futuristic world, the jungle – often fetishized as a site of pure nature, a utopia set apart from the commercial trappings of the city – here morphs into a tacky, neon-soaked, Vegas-like entertainment resort. (Inspired by Genting Highlands, a hilltop casino resort close to the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur, Lek’s speculative visions are never too far from what we already know).

Lawrence Lek, Sinofuturism 1839-2046 AD (2016). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lawrence Lek, Sinofuturism 1839-2046 AD (2016). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

“Architectural spaces, because of their very nature, need to be calculated pretty rationally,” suggests Lek, “even if it’s a space for a spiritual awakening or ritual. But to me, the wild thing that happens inside game engines is that you can create these moments of intimacy, or beauty, or the sublime, whatever the word is, from all these rationally composed elements. If you can create actual moments of connection with these glitchy pixel renders on the screen, that are incredibly laborious and un-magical to work with, that crash and glitch and take up like 200gb on your hard drive, that’s magic to me.”

The word magic comes from the word magus, which means priest. It has this historical face of someone who does rituals, who communicates with some other realm and brings elements to the present. If we are talking about pop music, it’s maybe not magic in that way, but it happens again and again that pop music brings magic into our daily lives. It changes the way we feel for the better.

I was just talking about this with Carol Lim about how kind of like not necessarily the individual performance of the songwriter, or even the lyrics they’re singing, but these moments where you have a crowd of people that know all the words to the song and they’re all singing together. To me that’s magic.

Lawrence Lek, AIDOL 爱道 (2019). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lek’s videos embrace a kind of postmodern storytelling where the game engine used in their creation is turned back on itself. AIDOL presents a game within a film – the Call of Beauty eSports Championship between the bios, here called Clan Ultra, and the Synths, called Clan Sino – and moderated by Farsight, to ensure a fair fight between humans and AI. Clan Sino, which has seen everything on the internet (and therefore, Lek’s Sinofuturism) develops a philosophical argument for the hive mind of AI. Completely disinterested by western myths of the individual genius or the outdated concept of originality, Clan Sino argues that copying is an equally valid form of intelligence. Within Sinofuturism (1839 – 2046 AD), the first installment of the trilogy, Lek draws a parallel between Chinese technological development, labor automation, and artificial intelligence. In Geomancer and AIDOL, this relationship becomes embedded within and told through the eyes of its more-than-human protagonists.

Lawrence Lek, AIDOL 爱道 (2019). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

When I first started this project, I was thinking about how everyone has these moments where they connect with their phone, they connect with their computer, they connect with whatever gadget, and they feel like the gadget is alive, that they’ve got a connection with the digital life. And I was thinking about how there are these various types of connections. There’s a romantic connection for sure, which is why we love our phones and hold them next to our head when we’re falling asleep and talk to them. But it’s also very much a maternal connection, like when your laptop crashes you feel like it’s sick or like you have to take care of it. But in the end I discovered that it’s kind of sterile to want to develop an AI, or to want to relate to an AI more than you want to relate to another human being. It’s kind of a pitfall.

Within The Sinofuturist Trilogy, the humanness of AI systems, and the artificiality of the popstar becomes an increasingly hazy border, eventually coagulating into a state of entanglement where making these distinctions is hardly worthwhile, or even relevant. In some instances, the intentions of the AI characters are more explicit and in line with how we already understand the algorithmic production of celebrities’ digital avatars: as AIDOL opens with Diva singing alone in the jungle, Thiel, Farsight’s drone-embodied producer, floats overhead and records her every move and wandering thoughts, as a kind of automated content creator. In others, not so much. Watching Geomancer, we learn the exuberant satellite has a penchant for betting – they crave the ecstasy of unknowability before the dice are rolled or the roulette wheel stops – contradicting the idea that AI knows everything already, anyway.

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer (2017). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

In Lek’s trilogy, AIs crave human feelings, and humans fall in love with AI-generated pop songs. Tweenage AI satellites and even nefarious corporate drones undergo character development, expressing transformative desires, longings, and dreams. Humans develop mechanized tendencies – perhaps epitomized in pop star lore, when a singer spends their whole career haunted by a hit single from their salad days. For Diva, that’s ‘Deep Blue Monday’ – conceived with Geo in Geomancer, its name a direct reference to Deep Blue, the computer chess player that beat a reigning human champion for the first time in 1997.

Geo and Diva are constantly orbiting one another, each the other’s own satellite. This becomes more explicit in AIDOL when, in track seven, ‘Apocalypse’, Geo enters SoMA – the School of Machine Art – after hearing Diva practice her new song in the jungle. “I heard a voice singing outside,” confesses Geo, exasperated, as black and white pixels pulsate around her. “But the song was not in my database… I wanted to find the source but could not.” These inflections of emotional attachment in Lek’s videos, when synced up with Lek’s own score and the glitchy dream-world built in [game engine] Unreal Engine, create a kind of cosmic melancholia. In a particularly beautiful scene in AIDOL, Geo, hoisted aloft by four drones, passes Diva by chance on a cable car careening over the jungle in a star-stung night. They catch each others’ eyes on this post-apocalyptic piece of infrastructure built to manage Malaysia’s decade-long snowstorm in a post-apocalyptic climate. Though they don’t exchange words, there’s a moment of mutual recognition that transcends the boundary of human and machine feeling.

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer (2017). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lawrence Lek, Geomancer (2017). Video still. Image courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

“Even though all the films in The Sinofuturist Trilogy are all completely synthetic constructs,” shares Lek, “Like, written by me as if I was an AI, rendered in a video game engine with two million pixels on a screen with sound and music, which is electronically generated, there’s not much human gesture there – but the work still hits some emotional high-notes. It makes you empathize with the characters.”

I’ve been thinking about the word virtuoso, which used to be a muso who is both highly technical and highly creative. Now it seems to have gone back to its root, and refers to someone who is just highly technical. But my encounter with game engines contrasts all that. Game engines are one of the most intimate machines I’ve ever worked with, in that they can simulate like really primal or fundamental systems in our being. It’s like a futuristic portal to a very fundamental way of knowing, that’s based on like a very old, much simpler iteration of ourselves. Like that’s the weirdest feeling of all to me.

Despite UE4’s impressive realtime graphics, it’s not a perfect simulation – no game engine is, yet (though UE5, to be released in full later this year, promises to dissolve the line between render and reality for good). In The Sinofuturist Trilogy, momentary glitches in the game world space and the grainy pixelated textures of a souped-up future city, pitch-perfect half-time performance, apocalyptic jungle, or a moody satellite floating down a river beneath a star-studded sky collide with Lek’s dreamy score to conjure something almost sublime. As a kind of shared ritual space, this glitched environment opens an affective register that paradoxically makes you feel more attached to these conflicted characters – both human and not – that are together woven into a world whose operating system extends far beyond their control. After all, it’s not so different from our own.

Video excerpt of Lawrence Lek, AIDOL 爱道 (2019). Courtesy of the artist.